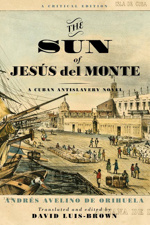

Today, we are happy to bring you our conversation with David Luis-Brown, translator and editor of THE SUN OF JESÚS DEL MONTE: A Cuban Antislavery Novel, out this week.

What inspired you to write this book?

Prior to 2007, Orihuela’s novel was virtually unknown; it typically only surfaced in scholarly footnotes in accounts of the martyrdom of the mulatto poet Plácido and in accounts of how Orihuela helped José Martí publish poetry in Spain while Martí was studying there in the early 1870s*.* But when I actually read Orihuela’s novel, it blew me away: this was no footnote—it was a major critical statement and a neglected landmark in Latin American literature that foregrounded the everyday struggles of free people of color in Cuba while opposing slavery, racism, claims of white “superiority” and even whiteness itself. I hope that this book will serve as a bridge that inspires my Anglophone readers to learn Spanish and read Latin American history and literature.

What did you learn and what are you hoping readers will learn from your book?

That visions of social change can emerge from critiques of whiteness. Eduardo, Orihuela’s semi-autobiographical main character, is like Orihuela himself an immigrant from the Canary Islands who is ostensibly white. Yet in conversation with a white overseer who expresses racist views, Eduardo claims an “African” identity based on his geographical origins and says he will always side with the oppressed. Orihuela could have led a fairly comfortable life as a lawyer without ever engaging in cultural critique. Instead, in his novel he chose to confront two of the most pressing issues of his time, slavery and racism. Orihuela would later become one of the founding members of the Sociedad Abolicionista Española (Spanish Abolitionist Society) in 1864.

What surprised you the most in the process of writing your book?

I was surprised that I was able to piece together a richer account of Orihuela’s biography by pulling together scattered snippets from his life in newspapers that I found in the Library of Congress, the Biblioteca Nacional José Martí in Cuba, the Biblioteca Nacional de España and the Bibliothèque nationale de France, among other places. The national libraries of Spain and France had thankfully digitized many of these sources—another surprise in itself.

Translating was another eye-opener for me. The process of translation ended up being even longer and more involved than I had imagined it would be. The work of translation necessitated an additional research project involving both historical and linguistic questions beyond the literary-historical research on the novel itself.

What’s your favorite anecdote from your book?

I’m fascinated by the moment in which the mulatta character Matilde learns that her white lover, Eduardo, has betrayed her by courting the title character, Tulita, a white woman known as the “Sun” of Jesús del Monte for her beauty. Eduardo intends to marry Tulita. Matilde responds to this personal affront by denouncing Cuba as an “unjust society” that has prohibited interracial unions. I like this moment in the book because it signals that Eduardo, despite his bold claims of African identity and his critiques of racism, is an antihero: he can talk the talk but he can’t walk the walk. Orihuela is pointing to the hypocrisy of would-be white reformers who oppose racism in theory yet are racist in their own everyday lives.

What’s next?

I am working on a new book project, “Antislaveries in Dos Hemisferios: Cosmopolitan Intimacies, Print Culture and Revolutionary Imaginaries of Blackness and Latinidad.” Lowe’s notion of “the intimacies of four continents” in the slave trade and capitalism has inspired me to investigate how various forms of intimacy—brought about through the shrinking of social and geographical distances in relationships, in workplaces, in forced and voluntary migrations, encounters in city streets and capitalist exchange—shape Black, Latinx and Latin American revolutionary imaginaries in an age of racial hierarchies and slavery. The book will examine antislavery sentimental melodrama and costumbrismo, Cuban antislavery writings, the formation of racially egalitarian notions of Latinidad in Spanish-language periodicals in Paris, and the decolonial imaginaries of Plácido, Martin R. Delany and Orihuela.