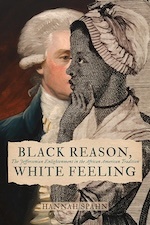

Today, we are happy to bring you our conversation with Hannah Spahn, author of Black Reason, White Feeling: The Jeffersonian Enlightenment in the African American Tradition

What inspired you to write this book?

My main inspiration was the richness and complexity of African American literary and intellectual history itself. If one were to rely solely on recent theoretical approaches such as "Afro-pessimism," one could sometimes get the impression that everything important has been erased from the historical record. From the eighteenth century onward, however, early American and African American print culture made possible one of the best-preserved, most sophisticated, and most influential minority literatures in the world, on slavery as well as a broad range of other topics. In my view, it's most of all the shared aspiration to do justice to this invaluable archive that can make today's discussions as productive and ambitious as possible.

What did you learn and what are you hoping readers will learn from your book?

My book differs from previous approaches in that it seeks to appreciate the differences between American and European Enlightenment traditions. For instance, "all men are created equal" didn't come into the world with Kant's categorical imperative attached to it. How then to understand the specific dynamics of Enlightened secularization in the United States? Studying the interplay between Wheatley's Enlightenment and Jefferson's Enlightenment has taught me to see Jefferson, not as a "false universalist," but as an epistemological nationalist whose self-conscious compromises with feeling, opinion, and prejudice are thrown into relief by the contrasting universalism of the African American tradition. Wheatley and her successors in turn emerge as the intellectual vanguard consolidating universalist ideas of human dignity by transforming Jefferson's transitional culture of opinion into the more fully secularized culture of knowledge in American modernity.

What surprised you the most in the process of writing your book?

I was stunned by the long shadow Jefferson's particular form of racism has cast over Wheatley's reputation, extending even to progressive contexts in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. His prejudice against Wheatley's poetry as supposedly derivative and inauthentic still resonates with many readers today, as does his allegation that it was "produced" by "religion," in the sense of a pre-Enlightened, somehow conservative worldview. His invention of "blacks" as an epistemologically separate nation, with its own supposedly incompatible ways of knowing, has proved equally tenacious. It seems to me that it's time to finally move beyond Jefferson's legacy on this point.

What’s your favorite anecdote from your book?

Having studied the revolutionary period for some twenty years, it wasn't until I zoomed in on Wheatley's Enlightenment that I realized who had shaped the idea of the "principles of the Declaration of Independence." Jefferson himself hadn't applied the term principle to the beginning of the Declaration's long second sentence; he had merely included it in its relativistic conclusion. For him, 1776 was a revolution in the "form" of government, not its "principles." His version of the Declaration should be given credit for replacing Locke's "estate" with "the pursuit of happiness," thus opening the phrase to antislavery uses. However, for the Declaration's universal rights to be seen as America's "saving principles," that is, as both the beginning and the foundational rule of the new nation, the original phrase's weak truth claims still needed to be transformed by the stronger concepts of reason and knowledge in the African American tradition.

What’s next?

I'm currently at work on two projects: one on American concepts of the generation and generational sovereignty, and another on the fin-de-siècle context of Charles Chesnutt, whose work has long fascinated me. Moreover, if ever I have the time, I'm hoping to edit the unpublished papers of the Berlin writer Hans Ostwald, a family relation from the early twentieth century. And, of course, the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence is coming up!