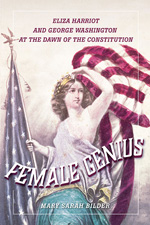

Today, we are happy to bring you our conversation with Mary Sarah Bilder, Author of FEMALE GENIUS: Eliza Harriot and George Washington at the Dawn of the Constitution, out today!

*************

What inspired you to write this book?

After I worked on my prior book on James Madison’s record of the Constitutional Convention, I could not forget an entry in George Washington’s diary while in Philadelphia in 1787 to attend the Convention. He heard a lady read at the College Hall. And he described her performance as “tolerable”—which is what Mr. Darcy says of Eliza Bennett. Who was the lady? Why was she giving a lecture? How could her story help us understand the relationship of women to the new constitutional system? I came to realize, and I want readers to realize, that 1787 was not about the small number of white men inside Independence Hall crafting a new system of government—there was a larger framing generation. It was a time of contingency, with some people seeking to codify existing inequalities and others dreaming of greater equality and inclusion. I wanted to tell the story of one dreamer—Eliza Harriot Barons O’Connor—whose influence may even endure in the gender neutral language of the Constitution.

What did you learn and what are you hoping readers will learn from your book?

I realized that the story of Eliza Harriot—a path-breaking female educator and lecturer—was also a history of a now forgotten argument about female genius. Eliza Harriot’s life turned out to parallel the history of expanding ideas about female education and political representation in England, Ireland, and the United States. She was born in Lisbon, Portugal, to British parents and married an Irish Catholic lawyer before moving to the United States in 1786. She embodied the aspirations of Mary Wollstonecraft, Catharine Macaulay, and other amazing women in the late 1770s and 1780s. But her life also reflected the backlash that women and people of color faced by the mid-1790s as white male elites explicitly excluded them from political participation.

What surprised you the most in the process of writing your book?

Eliza Harriot had a sentence in her advertisement for her ambitious female academy in Philadelphia in 1787: “The exertions of a female should … be considered … as presenting an example to be imitated and improved upon by future candidates for literary fame.” I had not appreciated this long tradition of inspirational female examples. Eliza Harriot’s emphasis on “improved on” highlights that she herself did not aspire to become, nor now needs to be understood as, a perfect model—but she did hope to inspire other women and girls to reach beyond their contemporary limits. This is why the book ends with the story of Charlotte Rollin, a Black woman born exactly 100 years later in the city where Eliza Harriot died. Rollin’s education and political ambition resembled those of Eliza Harriot—but Rollin emphasized the situation of Black women in her path-breaking speech before the South Carolina legislature in 1869 advocating for suffrage irrespective of sex.

What’s your favorite anecdote from your book?

In 1788, Eliza Harriot was living in Alexandria and running a successful female academy when her husband decided to leave for Edenton. She basically invited herself to Mount Vernon for several days to discuss her situation with George and Martha Washington. She noted that, “I am resolved in every situation to unite my best endeavors for our common benefit.” After receiving the invitation, Eliza Harriot explained that she didn’t have a carriage—and so Washington had to send one for her. Her confidence and lack of awe with regard to the Washingtons can be heard nearly 250 years later. She embodied and exemplified the refusal to consider oneself an inferior.

What’s next?

I find Washington’s diary of his time in Philadelphia during the Convention really interesting. Although he does not describe the Convention’s deliberations, one can find clues in his activities. In addition to having tea with lots of women, he visited most of the great country houses around Philadelphia and also returned to the sites of the disastrous Philadelphia campaign precisely a decade earlier, including Valley Forge. His memory of the war loomed large that summer. I want to think about Washington’s visits as a lens through which we can see that the Constitution as a system of government reflected both the experience of the war and the expanding economic and social prosperity afterward. Washington rode to a number of these places accompanied by William Lee, so this story necessarily intertwines with the status of Black Americans in this critical period.