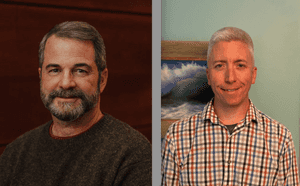

Today, we are happy to bring you our conversation with Rory McGovern and Ronald G. Machoian, editors of Race, Politics, and Reconstruction: The First Black Cadets at Old West Point

What inspired you to write this book?

There have been biographical works done on several of West Point’s first Black cadets and their arrival has been part of broader institutional histories, but none of these offered an in-depth study of the first attempt to integrate West Point, incorporating the complex perspectives of constituent groups and primary stakeholders. As historians working in this area in various contexts, we recognized an important gap in the scholarship – the absence of a more complete address of the Black experience at West Point during Reconstruction as an episode heavily influenced by the period’s social currents. We believe our project remedies this need. It brings together several accomplished historians in a volume that assesses West Point’s first integration efforts as a function of their times.

What did you learn and what are you hoping readers will learn from your book?

We hope that readers will come to understand the first effort to integrate West Point as both an experience and a process fundamentally connected to and shaped by Reconstruction itself. We also hope that readers will learn how groups and individuals in turn shaped the experience of integration at West Point, too often in ways that undermined its outcome and, in so doing, closed the door to Black cadets for many decades to come. And we hope that readers gain new appreciation for previously understudied actors in this story, especially James Webster Smith and others who have been at least partially obscured by the rightfully long shadow of Henry O. Flipper, West Point’s first Black graduate.

What surprised you the most in the process of writing your book?

Really that a similar work had not been undertaken to this point. The historical record is rich with materials that beg a robust telling of West Point’s important story as an actor on Reconstruction’s stage. As part of America’s struggle with race following the Civil War, the early Black experience at West Point is framed by the period’s dramatic struggle between federalism and regionalism; debate about education’s role as a social platform; and the influence of student culture and the failure of institutional leadership to shape that culture. The powerful story of Black cadets’ arrival there really demanded a full historical study, and this became even more evident as we worked alongside our contributors to sketch a framework for the volume.

What’s your favorite anecdote from your book?

One of the best anecdotes appears in Jonathan Bratten’s essay on the U.S. Army’s response to integration at West Point. Bratten found buried in William Tecumseh Sherman’s annual report in 1880. Sherman argued (unsuccessfully) that segregating Black soldiers to the famed Buffalo Soldier regiments was inconsistent with the 14th amendment, and that qualified recruits should be assigned to regiments without regard to their race. Sherman was precisely sixty-eight years ahead of his time in that recommendation, and he certainly was not known for being ahead of his time in issues of race. This anecdote is one of many in the volume that show people and institutions acting in unexpected ways that personalize and render more poignant what is otherwise a narrative of failed institutional change.

What’s next?

We are continuing other projects associated with the era, researching topics aligned with our interests in the evolving U.S. military profession as a cultural expression of the times and, in many ways, as a reflection of the broader historical narratives that carry and define American society. We hope Race, Politics, and Reconstruction offers a useful model and a valuable resource for historical research and teaching in the field, and we look forward to seeing what follows.