Capture the Flag

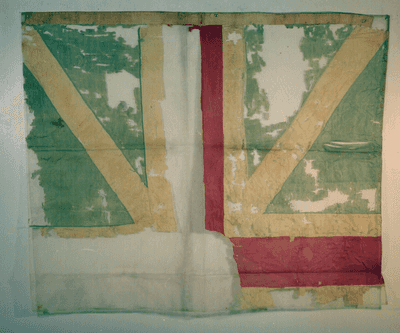

This is the only surviving British flag of the several captured by Bernardo de Gálvez during the American Revolutionary War. The flag was the only one that he kept for himself and was finally placed in his family’s mausoleum in the church of Macharaviaya, the Gálvez family’s hometown, in Andalusia. It was kept until 1903 when his descendants donated it to the Museo del Ejército (Spanish Army Museum).

A manuscript note in French, accompanying the case in which the flag was preserved, tells of a remarkable story.

“When the French wanted to enter the village during the War of Independence (1808-14), the population took this flag, and to the cry of ‘Gálvez!’, they drove back the enemy.” (Bandera británica capturada por Bernardo de Gálvez durante sus campañas en América, 1781. Museo del Ejército, no. inv. 40390.)

Unfortunately, no record has been found about the reaction of the French soldiers after being attacked by a group of Andalusian peasants rallied under a British flag.

During his campaigns in the southern theater of operations of the American Revolutionary War, Bernardo de Gálvez routinely defeated the British forces, beginning in Manchac, where he captured by surprise Fort Bute in September 1779. Shortly afterwards, Baton Rouge surrendered after a short siege. Having secured his rearguard alongside the Mississippi, and after returning to New Orleans for reinforcements~~,~~ in early January 1780, he departed for Mobile, which was also captured after a week-long siege.

Pensacola, the next objective, would not be conquered as easily as Mobile. Britain’s main stronghold in West Florida, Pensacola was well defended and prepared against a military incursion. Gálvez needed more troops and ships from Havana which were supposed to be sent to Mobile for the final push. Although reinforcements arrived in Mobile after its surrender, the size of the force was inadequate to ensure success. Gálvez had no choice but to return to New Orleans and then continue on to Havana. In Havana, the high command was extremely wary of Gálvez, whom they considered too young and inexperienced to be entrusted with such an important mission. A mission that~~,~~ furthermore, was deemed secondary to the defense of Havana, which, incidentally, had been occupied by the British in 1762-3.

Following protracted negotiations, an expedition against Pensacola left Havana in October 1780. But only two days after setting sail, a strong storm wrecked part of the fleet dispersing the rest throughout the Caribbean. When Gálvez returned empty-handed to Havana, his critics believed his career was over, but with the decisive support of the Secretary for the Indias, José de Gálvez, Bernardo’s uncle, he managed to prepare a new expedition, launched in late February 1781. This time the weather was fair and the fleet reached Pensacola Bay a few days later. After resolving a disagreement with the naval officer in command of the fleet, who initially refused to sail inside the harbor, the Spanish troops finally disembarked and lay siege, an effort that resulted in the capitulation of the British forces on May 10, 1781.

Between June 1778, when Spain declared war against Britain, and September 1783, when the peace treaties were signed, Bernardo de Gálvez captured more than a dozen British flags and standards, both from Army units and from British ships: four of them were on display in Santiago de Compostela’s cathedral as late as 1880; four others in the Basilica de Nuestra Señora del Pilar (Basilica of Our Lady of the Pilar) in Saragossa until at least 1920; several others in Seville’s cathedral disappeared sometime around 1812 when they were taken down in order not to offend the British allies after Napoleon’s defeat; those remaining flags were sent to Aranjuez and not seen after 1788.

While displaying captured enemies’ flags in public spaces was customary in continental Europe, it was unusual in the British Isles. Captured Spanish colors hanged over the Ridderzaal in the Binnenhof in The Hague, when the representatives of the seven regions of the Dutch Republic met in 1651 and decided that since the war was over, they did not need to appoint a new stadholder. Another instance was when in November 1914, during the first stages of the First World War, the French hanged eight German colors in the platform just below the organ of the cathedral of Saint-Louis des Invalides in Paris.

While in Britain, churches were embellished not with enemies’ flags but with their own country’s regimental colors, as even today in St. Patrick’s cathedral in Dublin with dozens of those standards representing the Irishmen who served in British units. The flags were, and still are, left to be hanged and decay as a tribute to the old saying that “Soldiers do not die, they simply fade away”. Although enemies’ flags were generally kept by the regiments who captured them, at least once however, the British did hang them in a cathedral. In 1806, for the solemn funeral of Lord Nelson in St. Paul's Cathedral, two huge Spanish and French flags flanked the coffin. To the left, the naval ensign, captured from the 74-gun Spanish warship, San Ildefonso in the battle of Trafalgar; and to the right probably the one taken from the Généreux, also a 74-gun, sunk in 1800 near Malta.

The image of the British tattered flag shows its original condition before being restored, in its present state one can observe that the renovation went beyond preserving the much-tattered flag and was mostly “recreated”, thus, in our opinion losing an important part of its original appeal. It perfectly represents the excellent performance of the Spanish Army during the American Revolutionary War, in which it was almost always victorious in land. The Spanish Navy did not enjoy similar success, but that is another story.

~Gabriel Paquette and Gonzalo M. Quintero Saravia, authors of Spain and the American Revolution: New Approaches and Perspectives

Image credits

British Flag captured by Bernardo de Gálvez during his campaigns in America. c. 1781. Bandera tomada en América por Bernardo de Gálvez en sus campañas americanas. Army Museum, Toledo, Spain, © Museo del Ejército, inv. n. 40390. Image licensed by the Spanish Army Museum.