Celebrating 70 Years of Rear Window: Hitchcock’s Mid-Century Masterpiece Comes Back to Life

Celebrating 70 Years of Rear Window: Hitchcock’s Mid-Century Masterpiece Comes Back to Life

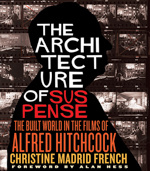

This year marks the 70th anniversary of Alfred Hitchcock's Rear Window, a film that has held audiences spellbound since it first hit the big screen in 1954. Recently, Rear Window had a limited re-release in theaters, giving new generations (and die-hard fans) the chance to experience it in all its grandeur once again. If you've never seen it—or even if you have—you'll find there’s always something new to discover in this tightly woven thriller. And, as I explored in my book, The Architecture of Suspense: The Built World in the Films of Alfred Hitchcock, you may discover that this film is a masterclass in using architecture as a main character that shapes the entire story.

The film follows L.B. "Jeff" Jeffries (James Stewart), a renowned photographer who finds himself stuck in his small New York apartment after breaking his leg during a daring shoot. With nothing but time on his hands, he begins to people-watch, observing his neighbors across the shared courtyard. From Miss Lonely Hearts, the sad woman who dines alone, to Miss Torso, the dancer who entertains men but seems to long for more, each window becomes a mini-narrative, a film within a film. With his glamorous girlfriend Lisa (Grace Kelly) by his side, what starts as a harmless game of voyeurism soon escalates into a sinister game of detective. Hitchcock turns us, the audience, into “watchers” too, making us complicit in Jeff’s game, all the while questioning what we see and what we think we see. Are we witnessing a murder, or just a string of coincidences?

Hitchcock’s choice of setting—Greenwich Village—was no accident. The film's backdrop is a meticulously designed set, based on a real-life courtyard at 125 Christopher Street in New York City. The building is a tribute to the architectural genius of Hyman Isaac Feldman, an Austrian-born architect who made his mark with over 2,500 designs, each bearing his distinctive touch, like the angled corners of the Christopher Street complex. This layered, urban environment gave Hitchcock the perfect canvas to explore his themes: the ambiguity of perception, the blurry line between observation and invasion, and the complex interplay between private and public spaces.

Hitchcock's decision to recreate the courtyard on a massive Paramount set was nothing short of visionary. With the help of art directors Hal Pereira and Joseph McMillan Johnson, Hitchcock built a fully functioning microcosm of the city on Stage 18—complete with twelve fully furnished apartments, working plumbing, and a Manhattan skyline looming in the background.

Interestingly, the existence of the real-life building at Christopher Street today is, in part, thanks to Jane Jacobs, the renowned urban activist who lived just a few blocks away at 555 Hudson Street. Jacobs, author of The Death and Life of Great American Cities, became a powerful voice in preserving the character of Greenwich Village against the threat of urban renewal in the 1960s. Her advocacy helped save the neighborhood's unique architectural fabric, ensuring that the backdrop to one of cinema's great thrillers remained intact for future generations.

The attention to architectural detail in Rear Window was not just about aesthetics; it was about creating an environment where every corner, every window, every shadow could harbor secrets. Hitchcock’s use of the Kuleshov effect—a technique of using editing to manipulate the audience’s perception—keeps us guessing until the very end. Is the murderer actually guilty, or are Jeff and Lisa letting their imaginations run wild? In this layered urban setting, nothing is ever what it seems.

Rear Window may have been snubbed by some critics of its time, with The New Yorker calling it “another example of [Hitchcock’s] footless ambition,” but the film has since secured its place in the canon of great American cinema. As the Boston Globe rightly observed, Hitchcock knew what audiences wanted—a spine-chilling climax. And he delivered.

Seventy years on, Rear Window remains a timeless exploration of human curiosity, desire, and the art of watching. So, if you find yourself with the chance to see it again on the big screen, don’t miss it. After all, Hitchcock’s Greenwich Village isn’t just a set; it’s a world—a little universe where every window has a story to tell.

—Christine Madrid French

QuickLinks

Find a BookFor Our AuthorsRights and PermissionsRotunda Digital ImprintSupport UVA PressCareer OpportunitiesWalker Cowen Memorial PrizePrivacy PolicyContact Us

- P.O. Box 400318 (Postal)

- Charlottesville, VA 22904-4318

- 210 Sprigg Lane (Courier)

- Charlottesville, VA 22903-2417

- 434 924-3468 (main)

- 1-800-831-3406 (toll-free)

- 434 982-2655 (fax)

the future

of publishing

Affiliates