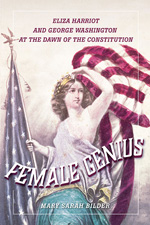

Happy Presidents' Day! Celebrate by Reading an Exclusive Preview of FEMALE GENIUS: Eliza Harriot and George Washington at the Dawn of the Constitution by Mary Sarah Bilder

Happy Presidents' Day! Celebrate by Reading an Exclusive Preview of FEMALE GENIUS: Eliza Harriot and George Washington at the Dawn of the Constitution by Mary Sarah Bilder

I met Eliza Harriot—I did not know that was her name—many years ago. Over the years as I have studied the convention, one entry in George Washington’s diary from May 1787 nagged at me. The convention was supposed to start on Monday, May 14. Washington arrived in Philadelphia the day before and waited as delegates slowly trickled into town. He drank tea at Robert Morris’s house: “The State of New York was represented. Dined at a club at Greys ferry over the Schuylkill & drank Tea at Mr. Morris’s— after wch. went with Mrs. Morris & some other Ladies to hear a lady read at the College Hall.” He capitalized the first “Ladies,” and left the lady herself lowercase, implying a distinction between the anonymous lady and Mary White Morris, the spouse of financier and delegate Robert Morris, and her friends, possibly including Elizabeth Willing Powel. Who was this lady? What was she doing giving a lecture at what later became the University of Pennsylvania? What relationship did she have to the Constitution and the framing era?

This book recovers in full the life of this one woman, Eliza Harriot Barons O’Connor, an educator and advocate for female capacity, and to an extent that of her spouse, John O’Connor, a lawyer by training, and tells their story to illuminate the ways in which the developing American constitutional state confronted and eventually excluded people based on sex. I approach this period through the lens of constitution and as part of the Age of the Constitution. Her presence reveals the view of female education represented by Benjamin Rush and other writers associated with “republican motherhood” as a centrist, conservative argument. The critical year—1792—becomes here a moment in a rising transatlantic trajectory with education as the foundation of female participation in the constitutional state, rather than the starting point in a narrative about women’s political rights. By viewing Eliza Harriot’s life through this lens, we can see the crucial analytical relationship among education, suffrage, and officeholding. And we can reflect on the fluid and shifting arguments that created nineteenth-century female disenfranchisement and its long legacy. . . .

In seeking to reframe the constitutional politics of gender in the 1780s, I do not deny the pervasive view throughout this period of the state as white male gendered. Washington’s relationship to the conventional understanding of women in relation to American political power appears in Edward Savage’s The Washington Family. Here we see Washington, his wife, her grandchildren, and an enslaved Black man, with a less precisely detailed face, possibly William Lee. The omission of a figure representing enslaved women—for example, Ona Judge, who would escape from the Washingtons in 1796—furthers the racial and gender hierarchy. Washington’s political power appears in conversation with his blended family and the representation of enslaved dependents. And Savage’s arrangement places the two white men on one side and the women and person of color on the other to emphasize who—hand on the globe—holds power. George gets a sword; Martha a fan pointing to “the grand avenue” (Pennsylvania Avenue), the location of the future White House. She has a certain type of power, but it appears domestic and subordinate, in the same class as young girls, servants, and the enslaved. The patriarchal family is here the patriarchal country. This view was loud and ever present. Had there been polls in the 1780s and 1790s, perhaps they would have reflected the view’s dominance.

George Washington’s presence in the subtitle of this book and his reappearance throughout the narrative serves as a constant reminder of that reality. Eliza Harriot’s 1787 lecture in Philadelphia received widespread newspaper coverage because of Washington’s attendance. Her letters survive because she wrote them to him. Moreover, Eliza Harriot recognized Washington’s political and cultural power and enlisted it for her purposes. As a sophisticated observer of the patronage politics of the Atlantic world, she repeatedly sought Washington’s public approbation of female genius. The realities of political power barred her entry from employments and appointments that would bring the fame to justify a solely self-titled biography. As “Mrs. O’Connor,” her story might be ignored as that of one failed female schoolteacher’s tale. In contemporaneous newspapers, she appeared as “The Lady”—an anonymous descriptor she herself chose, one that represented both herself and unknown others. In the title, she is Eliza Harriot—the first name that she used in her correspondence and the only one over which she had personal control. Her intertwined path with Washington mirrors the inextricable relationship between gender equality and political authority in this period.

Eliza Harriot shows us that there were other strands and beliefs competing with the white, male political vision represented by Washington. People lived their lives to make real a counter-vision. Historical writing is not always particularly good at demonstrating what we know to be true about our own time, that there are many voices. The one that seems to hold power is not the one that may reflect our deepest commitments or the path by which many live their lives. This erasure of multiple voices is, of course, exacerbated by the privileging of the published record and of private papers of public figures. But it was a framing generation that created the Constitution as a system of government.

During the 1780s, in England, Ireland, France, and the new United States, glimmerings could be found of the belief that women were full persons, with equal intellectual capacity, deserving of education, capable of debating politics, and able to occupy public rhetorical spaces conventionally reserved for men. Intriguingly, the Constitution was drafted in this space with dynamic possibilities. And Eliza Harriot’s presence in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787 provides evidence that the stylistic, gender-neutral formula used to describe officeholders was a response to this broader expansive vision about women’s role in the political state.

QuickLinks

Find a BookFor Our AuthorsRights and PermissionsRotunda Digital ImprintSupport UVA PressCareer OpportunitiesWalker Cowen Memorial PrizePrivacy PolicyContact Us

- P.O. Box 400318 (Postal)

- Charlottesville, VA 22904-4318

- 210 Sprigg Lane (Courier)

- Charlottesville, VA 22903-2417

- 434 924-3468 (main)

- 1-800-831-3406 (toll-free)

- 434 982-2655 (fax)

the future

of publishing

Affiliates