Remembering Stephen Sondheim: An Original Post by Sharon Aronofsky Weltman, Author of VICTORIANS ON BROADWAY

Remembering Stephen Sondheim: An Original Post by Sharon Aronofsky Weltman, Author of VICTORIANS ON BROADWAY

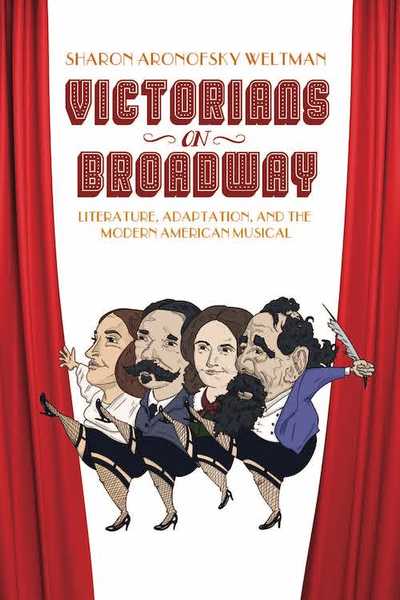

Thanks to Sharon Aronofsky Weltman, author of VICTORIANS ON BROADWAY: Literature, Adaptation, and the Modern American Musical, for this original reflection on the life and work of Stephen Sondheim.

*************

On Friday after Thanksgiving, I never shop. I’ve never been a Black Friday shopper, not even before the pandemic made the idea scary. Instead, I hang out with the family I’ve flown to see, making turkey soup and joining my husband and niece around the piano for show tunes—he plays, she sings, both extremely well. She’s a mezzo. This year it was a joyous visit, cozily together again after two years. Little did we know when she gave us the Baker’s Wife’s “Moments in the Woods” (from Into the Woods) that I was hearing what became—in my mind, at least—the first of many tribute songs to great composer-lyricist Stephen Sondheim, whom the world lost earlier that day.

Like everyone mourning Sondheim, I have always been a fan, not from my first cigarette (I’ve never smoked), but certainly till my last dying day. While I don’t have the chops of the stars Lin-Manuel Miranda led in “Sunday” from Sunday in the Park with George in Duffy Square on November 29th (all of whom have performed Sondheim one way or another), I have exercised what talents I do have—research and writing—in working with his genius in other ways, devoting a chapter to Sweeney Todd in my book Victorians on Broadway: Literature, Adaptation, and the Modern American Musical (published by UVA Press in 2020). It was an extraordinary honor to interview Sondheim for it. I literally fell off my chair when I first saw “STEPHEN SONDHEIM” in my email inbox, and I do not use the word “literally” in a figurative sense. Our correspondence started a little stiffly with titles and honorifics, but we ended up with Sharon and Steve. He was wonderfully gracious. One thing he said that I will describe made the whole book—not just the chapter on Sweeney Todd—much better.

In Victorians on Broadway, I examine Broadway musicals based on Victorian literature, such as Oliver!, The King and I, Drood, Jekyll and Hyde, and of course Sweeney Todd. I examine aspects of novels by Charles Dickens or Robert Louis Stevenson that predispose them to musical theater adaptation, and I examine how adapters use these books to perform cultural work for the moment of performance. The book argues that no matter who wrote the source text (whether Charlotte Brontë or a penny-dreadful hack), once a Victorian tale becomes a Broadway musical, it brims with characters, themes, and a mise-en-scène that recall Dickens or prior adaptations of Dickens. An example is the relationship between Sweeney Todd and Oliver!, a musical that Sondheim told me that he did not see as a precursor to his own. And yet there are surprising similarities. For example, Sweeney Todd imports the large singing Beadle Bamford, a villainous tenor, into a narrative that included no Beadle of importance in the source. Where did he come from? Mr. Bumble, another villainous tenor Beadle, is a very large presence in Oliver!

And who corroborated this argument? Sondheim himself. I asked him what he thought of or pictured when he envisioned Victorianness, and he answered “I just hear Dickens, I think Dickens. Dickens movies I’ve seen, and the couple of novels of his I’ve read.” Not only for Sondheim but for Broadway in general, Victorian equals Dickensian.

In addition to giving me this wonderful quote that sums up the book’s argument, Sondheim gave me something else through the format of our interview. I emailed him my questions, and he recorded his answers to them over a period of several weeks between about December 19 and December 25, 2012. I expected an mp3 file by email, but instead, around January 14, 2013, a cassette tape arrived by snail mail. There it was, in my hand, with my name on it in his handwriting. I found an old tape recorder to play it on and listened with my laptop recording it at the same time, just in case the tape broke the very first time it was played. When Sondheim signed off by wishing me a merry Christmas, his voice stopped—and a woman yodeling began. He’d simply taped over an old recording of someone’s virtuoso yodels of classical music. In other words, I could say that Sondheim gave me a mix tape.

That moment of laughter when the yodeling commenced is another gift from this towering figure whose works from West Side Story to Road Show I will cherish to my last dying day.

QuickLinks

Find a BookFor Our AuthorsRights and PermissionsRotunda Digital ImprintSupport UVA PressCareer OpportunitiesWalker Cowen Memorial PrizePrivacy PolicyContact Us

- P.O. Box 400318 (Postal)

- Charlottesville, VA 22904-4318

- 210 Sprigg Lane (Courier)

- Charlottesville, VA 22903-2417

- 434 924-3468 (main)

- 1-800-831-3406 (toll-free)

- 434 982-2655 (fax)

the future

of publishing

Affiliates