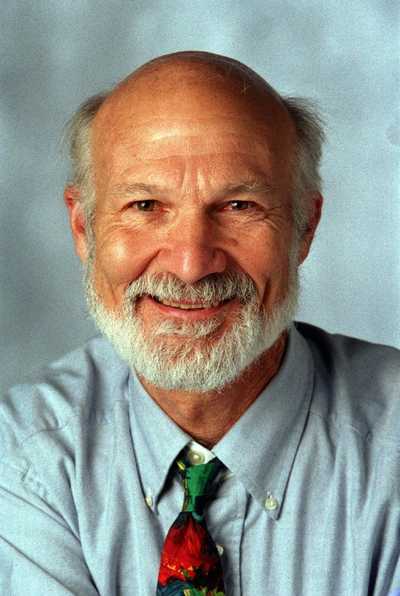

Stanley Hauerwas, author of Fully Alive, Receives 2022 Lifetime Achievement Award from The Society of Christian Ethics

Stanley Hauerwas, author of Fully Alive, Receives 2022 Lifetime Achievement Award from The Society of Christian Ethics

As Duke Divinity School reports, The Society of Christian Ethics recently announced that Stanley Hauerwas, Gilbert T. Rowe Professor Emeritus of Divinity and Law and author most recently of FULLY ALIVE: The Apocalyptic Humanism of Karl Barth, has been awarded the 2022 Lifetime Achievement Award.

With permission, we have included Professor Hauerwas's acceptance speech below.

On Receiving the SCE Lifetime Achievement Award

Stanley Hauerwas

“I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth”—Lou Gehrig. Though I never aspired to be a first baseman for the Yankees—Jon Stock must bear that burden—Gehrig’s sentiments expressed at his retirement due to his ALS illness says what I feel on being recognized by the SCE. My only hesitation by expressing myself using Gehrig’s words is Christian ambiguity about the concept of luck. Impressed by the sheer contingency of our lives, we are born and then we die, the Stoics learned to live without resentment. The Stoics were morally impressive, but I am not a Stoic. I am a Christian.

The difference Christianity makes is expressed by Gehrig’s next sentence that explains why he feels so lucky. “I have been in ballparks for 17years and have never received anything but kindness and encouragement from you fans.” The Society of Christian Ethics is not exactly a ballpark but it is one of the fields on which I have played. I cannot say as Gehrig does that I always received from members of the SCE the kind of encouragement he enjoyed from fans in the many ballparks in which he played. Yet I am sure playing at the SCE made me a better fielder. It is true, however, that I still cannot hit a curve ball.

I am still working but extra innings do not last forever. I have already had more extra innings than many. As you might expect I am not good at knowing how to come to an end. But in The Art of Worldly Wisdom, Baltasar Gracian, the worldly-wise Spanish Jesuit, advises:

Make yourself wanted. Few have won popular favor; consider yourself fortunate if you can win the favor of the wise. People are usually lukewarm toward those at the end of their careers. There are ways to win and keep the grand prize of favor. You can be outstanding in your occupation and in your talents. A pleasant manner works too. Turn eminence into dependence, so that people will say that the occupation needed you, and not vice versa. Some people honor their position, others are honored by it. It is no honor to be made good by a bad person who (may) succeed(s) you. The fact that someone else is hated doesn’t mean that you are truly wanted.

It is tempting to describe Gracian as a cynic but I think that a mistake. He is rather an insightful commentator on the human condition. I should like to think that I may have said or written something from time to time some of you found useful if not insightful. I was recently introduced by a friend who suggested that once you see what I have seen you cannot unsee it. That which cannot be unseen I hope makes possible insights that not only enrich our work as Christian theologians and ethicists, a division of labor I have long resisted, but might even help us to live lives of virtue.

That our work as theologians and ethicists might have something to do with how we live can be dismissed as pretentious bullshit. MacIntyre, for example, challenges the presumption that the teaching of ethics might make students ethical by asking if you can observe any difference the teaching of ethics makes on those that do the teaching. MacIntyre presumes we would find it hard to answer that question in the affirmative.

That such is the case I think is a major challenge for the future of the SCE. The challenge being whether we know what we are doing when we teach ethics. Are we trying to help those we teach as well as ourselves know how to be better human beings? If so by what authority do we undertake that task? Moreover if insight is a characteristic of those who are good how do we become as well as train others to be insightful?

Before we can make headway on that those questions we have to ask if we have any idea what makes an insight an insight. Insights seem to come from nowhere but once articulated the insight seems obvious. The grammar of the language used to express the insight, moreover, is constitutive of the insight. I think many of us became ethicists because of insights learned from the study of those with whom we may even disagree but who have said what we cannot help but think is true. Which raises the question from where do insights come? Are they dependent on the training a person receives or do they reflect the humanity that some people seem to have?

I recently received a lovely letter from a graduate of Duke Divinity School reporting that by reading some of my work I had become an unsettling yet comforting voice in her head. According to her I have challenged what many assume are the givens by doing something as weird and angular as questioning word usage. She compares the way I think to a plane that comes in from an unexpected direction but is nonetheless able to land upside down. I always find such letters humbling and frightening suggesting as they do something I have written may have screwed up someone life.

My correspondent continues by suggesting that, like Emily Dickinson, I think on a slant. She then asks how can she learn to think in a similar fashion? Are there habits or texts in order to learn not just what I do, but how I do it? I would love to know how to answer her but I am not sure how to say what I have done or how I did it. My best advice is to ask those who have studied with me. They often know the what and how to do what I have done better than I do.

That I am often unable to say how I came to say what I have said this way rather than that way I take not to be a bad thing. After all it gives me and all of us that make up the SCE something to do. And what could be a better gift as we approach death than having good but never finished work to do. So engaged we might even become at this late date just a bit better human beings. At the very least I know the friends that have claimed me through the SCE have made me more than I otherwise would be. Which is why this award means a great deal—thank you for such a recognition. Photo courtesy of Duke Divinity School.

QuickLinks

Find a BookFor Our AuthorsRights and PermissionsRotunda Digital ImprintSupport UVA PressCareer OpportunitiesWalker Cowen Memorial PrizePrivacy PolicyContact Us

- P.O. Box 400318 (Postal)

- Charlottesville, VA 22904-4318

- 210 Sprigg Lane (Courier)

- Charlottesville, VA 22903-2417

- 434 924-3468 (main)

- 1-800-831-3406 (toll-free)

- 434 982-2655 (fax)

the future

of publishing

Affiliates